Introduction

Back to the first article and the table of contents

Ah concurrency, the gift that keeps on giving. You’ve likely read the articles about concurrency vs parallelism, but have you really given much thought to what it looks like at scale?

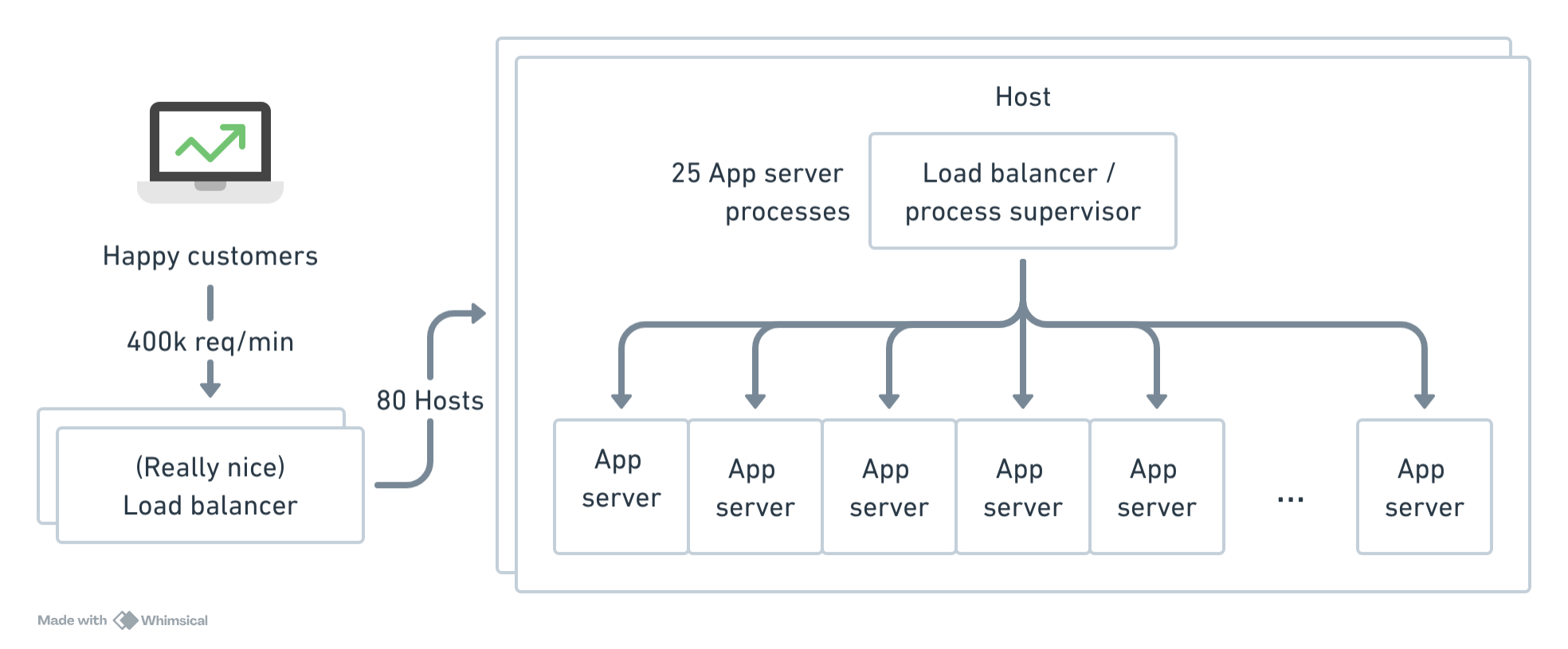

How do the concepts of concurrency and parallelism apply when you have 80 physical machines with 2000 processes between them (spoiler, it doesn’t matter)? Does anything even change or does it act like an aggregate 640CPU machine (spoiler, it pretty much does)?

I’m not sure the point where it changes, but at some scale, neither of those questions really matter anymore. We start worrying about other things that you wouldn’t even think to care about.

What I really care about is:

- What is the transit duration through my service?

- How many secret queues are holding requests hostage (spoiler: waaaaay too many)?

- How can I get monitoring info out of these?

- How much are we relying on timeouts for reliability (spoiler: too much)?

- How many secret retries are set up throughout my stack (spoiler: too many)?

So I can say with some confidence that even though I immediately forgot everything I learned about concurrency and parallelism in college and at work, it hasn’t actually been too much of a problem! [ed: There are probably some epiphanies he had that he’s forgotten about, and you should strive to have those too, whatever they were.]

“High-scale” vs “Hyper-scale” architectures

I’ve seen some job ads recently that say “HyperScale Candidates Only”. I don’t know what that means, but I don’t think we’re talking about that.

I think “High-scale” means that you can get away with a single load-balancing thingo in front of your app. It may be a big load balancer, it may have hot spares, but it’s not the thing limiting you. We can handle 400k req/min with a nice pair of F5 load balancers.

Similarly, we’re at a scale where bandwidth is still plentiful, disk space is managable, and we aren’t bumping up against the hard limits of what EC2 or S3 can deliver (at least, our team isn’t). The database is probably your biggest problem. And all those external services that the app needs to talk with. And oh god, Engineering Leadership or Agile Transformations. But at least it’s not the load balancer.

For “High-Scale”, you can think of your app as a single machine with 640CPUs, 3.2TB RAM, and enough bandwidth to service a country.

While it’s obviously not true that it’s a single aggregate machine, and you will have problems that are related to single machines going rogue or whatever, for the purposes of thinking about concurrency, it’ll be fine.

So what does “Concurrency” mean at this scale?

For the purposes of our series, “concurrency” (I’m going to drop the quotes from here on in) means:

Concurrency is the number of active requests present in the entire system at this moment in time.

By active requests I mean requests that aren’t sitting in a queue in the load balancer. They’re doing something meaningful, costing some CPU somewhere. They may be sleeping in your service, but they’re doing some work in the database or some other external service and your service has a connection open.

By the entire system I mean all the machines that are dedicated to serving this one specific app’s traffic, including external services and databases (even if they aren’t in your datacenter or even owned by you). But it excludes traffic unrelated to this specific app.

By this moment in time I mean this moment; not “aggregated on a minute boundary”. This is actually the hardest part. Most observability companies only provide you aggregate info, which is helpful for stats and charts, but we need to make decisions in the instaneous values.

Little’s Law

Look, I’m not going to go into Little’s Law. It’s a mindf*ck when you really get in there. I’m going to give you the simple version:

Little’s Law: If you have a high (but sustainable) load of incoming requests, and the processing time of your service increases, your service will die.

Here’s some correlaries/examples:

- If the service is dying, number of connections to the load balancer will start increasing.

- If an external service slows down, your service will die.

- If you add an index in the database live, which slows it down temporarily, your service will die.

- If you release and enable sufficiently slow code, your service will die.

- If a 500 page takes longer to render than the original page that was requested (don’t judge, it happens more than you think!), your service will die fast.

- If your

/healthCheckendpoint has a database call (or external), and the database goes down (or slows down), your service containers will be killed and your service will die.

But these are all subsets of Little’s law. Written another way:

Little’s law part 2: When the processing time increases, the number of processes doing work increases, until the service passes some point and stops responding.

The great thing about this is that Little’s Law tells us everything we need to know.

We need to know the number of active requests (and whether that’s increasing to an unsustainable level) in the entire system (and whether that number is changing) at this moment in time (not delayed and aggregated, because we need to be able to act now).

Sounds familiar eh?

Why we can’t have nice things (and what we can have)

But here’s the rub: It’s impossible in most architectures (except Elixir/Erlang). Or at the very least, it’s inadvisable.

Sad. Thanks for reading! Like and Subscribe or whatever…

Sorry, let me try again. It’s impossible because knowing the concurrency of the entire system would require network communication with some coordinating body, a redis or something. When we’re dealing with flakey network stuff or the db team is maintaining the Redis clusters:

We absolutely cannot have our core reliability primitive relying on a network call.

But we can at least track concurrency on the machine. At least among those 25 processes or threads, we can find out how many are processing active requests. We can also ask the load balancer how many requests are waiting to be processed.

Little’s law (3rd time’s the charm!): If the load balancer is holding a lot of requests, it probably means your service is dying.

Between the load balancer and each individual machine’s concurrency number, we can send those numbers to our observability tool of choice and start to add some real alerting oomph to our stack.

By the end of this, you’ll be able to:

- Set alerts on the ingress concurrency and very accurately determine whether the service is at failure state

- Set alerts on the egress concurrency to each external and accurately determine if any of them is at failure state

- Set limits on individual users or cohorts of users that are informed by the overall system state

And hopefully we’ll be able to get you out of pager hell.