Introduction

In this post I’d like to teach you a little bit about server concurrency tracking. I’m going to assume that you know what concurrency is and the difference between concurrency and parallelism, but I want to talk about “concurrency tracking”, how this applies to backend web servers, and how it applies at scale.

This article series is targeted at fairly senior engineers. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t read it if you aren’t a senior, but that if you aren’t already senior, you should come prepared to ask for help.

Summary

Here’s what we’re going to talk about:

- In the context of server observability, “concurrency tracking” is really about how many requests are active in the entire architecture in one specific moment.

- This is further subdivided into many facets, but we’ll talk about those later.

- We need to focus on the longest period of peak-throughput “normalcy” we can find.

- We need to be way more careful when applying limits than one would normally expect.

So what is concurrency tracking then?

It’s definitely related to concurrency and parallelism, but at the scale of a company

Concurrency tracking is focused on how many requests are active in the entire architecture in one specific moment.

In order to do this, we need some way of tracking what an “active request” is. To be clear, we’re not talking about requests that are queued up waiting to be handled, nor are we talking about requests that are blocked waiting on responses from network resources. We’re talking about requests that are actively being worked on, right now.

While that’s possible to do on a single process or maybe even a single server, how do you do it when you have thousands of processes?

A physical representation of an “active request”

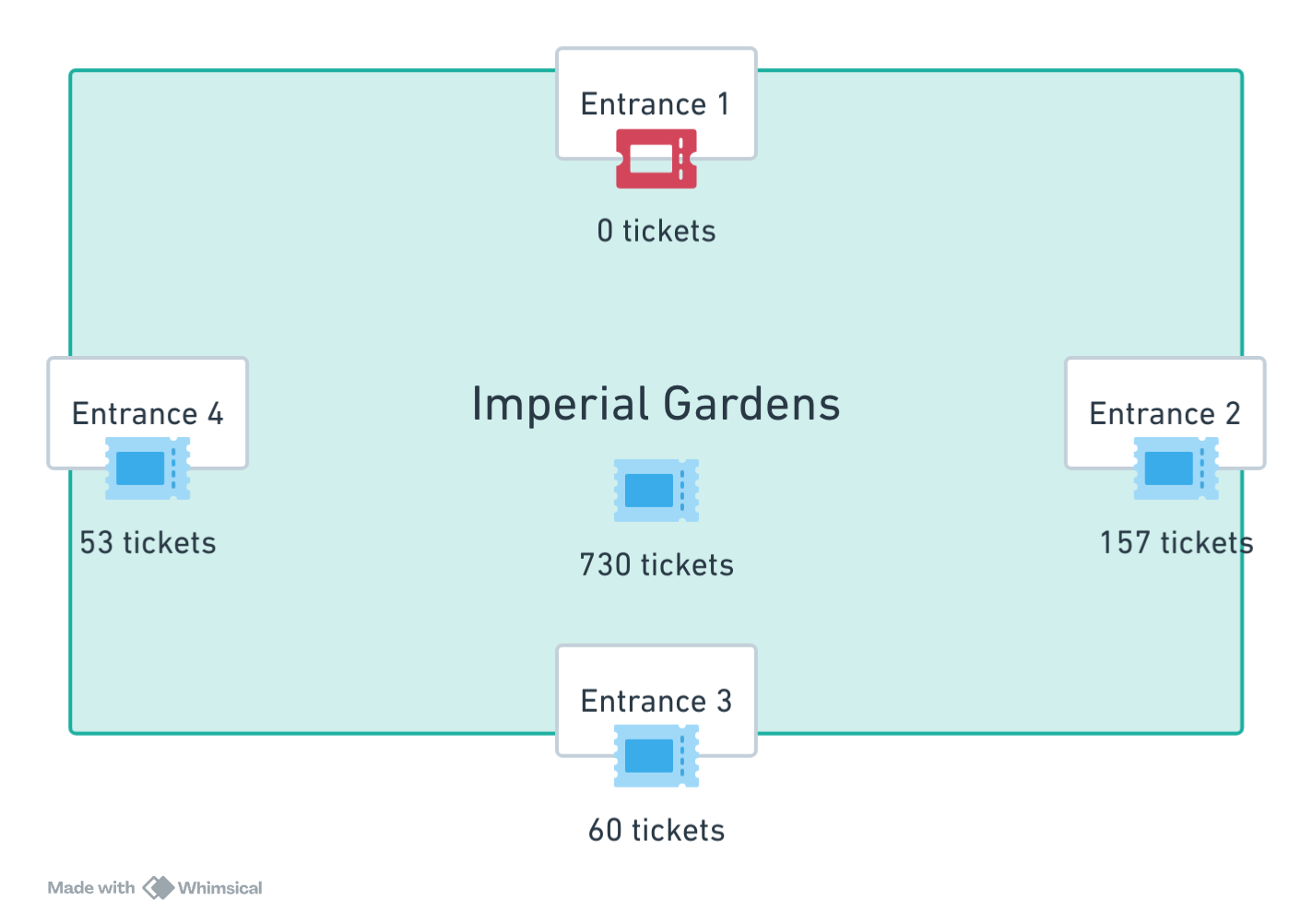

There’s a story that Taiichi Ohno, the father of Kanban and the Toyota Production System, observed a novel ticketing system at the Imperial Gardens of Japan. The story goes that when he arrived at the garden he was given a ticket. The tickets do not cost money to acquire, but when you finish your visit you are asked to give your ticket back. He asked what happens if there are no tickets left, and they told him that in that case, he would have to wait until there was a ticket available.

This system ensures that there are no more than n people in the park at any given time, because there are only n tickets distributed between all the different entrances.

If you’ve been to a big concert or festival or night club, you will have seen the bouncers counting how many people are inside and only letting new folks in when the club is below max occupancy. But this only works because there’s only one entrance.

Take a moment to imagine what it would look like if you had 4 entrances. You would have to have some means of communicating back and forth about whether to let in the next person or not. It would be a mess!

With a ticketing system, we can guarantee that the system is not past occupancy limits. Even if you have thousands of gates.

This ticketing system is a great model for part of the problem we have as well:

- There is only so much traffic our system can manage.

- When there is too much traffic, we see queues start to form up.

- If a queue is too long, additional problems present themselves (like the line snaking into traffic or blocking access to businesses.)

Finding the right numbers

At the Imperial Garden they already know the max capacity, probably because of rigorous study and lots of engineering. Here in the USA, the fire inspector will tell us the max capacity of small spaces, but we have to do similar engineering for larger spaces.

Unlike the typical business however, software is not constrained by how many people need to shuffle through the doors in the event of a fire. We fundamentally do not know the maximum capacity of our system in the same way. But we do know that there’s a limit, and very likely if you’re reading this you’ve tripped over that limit at some point or another.

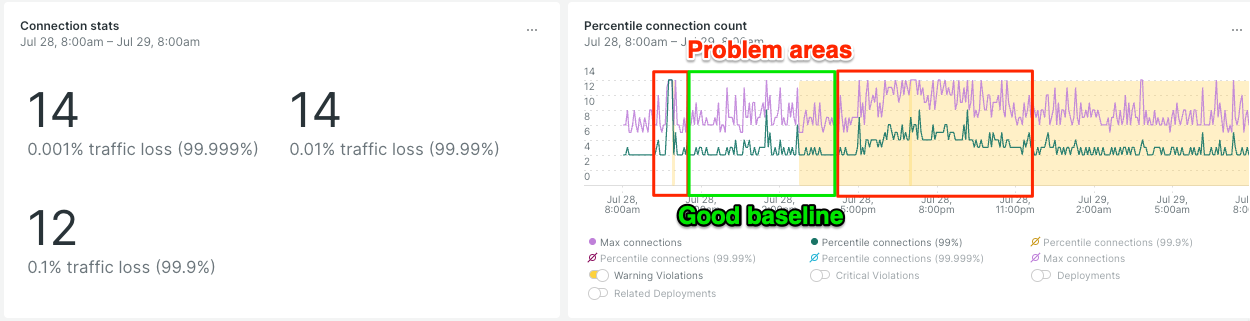

While this will not apply for some systems, we can at least start by giving out infinite tickets and tracking exactly how many get used at once and for how long. In a previous article, I used this baseline image to demonstrate the trickiness of finding a good number:

In the above graphic, we want to find the longest peak throughput period with no abnormal behavior. We want it long, because that will filter out noise, but we want it “normal” because we specifically want to capture the abnormally high periods.

I’m not going to go into Little’s law, but I do want to pull one thing from it and that is:

There is a strong correlation between increased concurrency numbers and increased system problems.

How does this apply at scale?

There is an epiphany that I’m not sure how to communicate, but I’m going to do my best.

There are going to be times when your load balancer unfairly distributes work to one machine. Customers are going to do… interesting things. Servers are going to have slow moments, maybe when they deploy, maybe when they do garbage collection or purge files. How can you capture all those normal situations?

But also, your app is probably not isolated; it exists in an ecosystem of other apps. We need to consider how limits applied at one node can impact the other nodes in the system.

The epiphany I need you to have is that:

The line between incident and normal is much finer than you think.

You must not start limiting until you have this epiphany and know how to deal with it.

If you use a 99th percentile function to calculate the max capacity, which might seem totally reasonable, you will end up dropping 1% of your traffic and it will feel absolutely arbitrary and random.

When we talk about limits, we need to assume that 100% - target% is an amount of traffic we’re okay dropping completely at random. So we’re going to do a lot of 99.999th percentile stats in the coming articles.

Even if some incidents make it through, overlimiting is worse than underlimiting when it’s applied to a company-wide architectural scale.

Conclusion

So there you go: concurrency tracking. I hope you’re interested and want to read more!

Here’s a summary again, do you feel like these make a little more sense now?

- In the context of server observability, “concurrency tracking” is really about how many requests are active in the entire architecture in one specific moment.

- This is further subdivided, but we’ll talk about those later.

- We need to focus on the longest period of peak-throughput “normalcy” we can find.

- We need to be way more careful when applying limits than one would normally expect.