Introduction

When bulkheads and circuit breakers work together, one struggling external service or database will no longer take out your entire service.

This article exists to help you find the right configuration for your bulkhead system of choice before finding out the config is insufficient for production loads.

Bulkheads can be implemented in many different ways and at a lot of different levels, so I’ll try to cover the general process for finding the right config. But because we all know it’s helpful to have a specific example, I’ll talk about the Ruby library Semian in this article.

Semian is a unified, low-effort tool that adds circuit breakers and bulkheads to most network requests automatically. It covers http, mysql/postgres, redis and grpc out of the box.

There are a lot of articles describing bulkheads/connection pools and circuit breakers, but remarkably few about how to tune them. I’ve found a few lonely articles on tuning circuit breakers, but I’ve found zero about tuning bulkheads and connection pools.

The problem here is that a poorly tuned bulkhead can be catastrophic. Worse, the problem can be subtle and hard to detect, only affecting maybe 0.1% of traffic in a maddeningly random way.

I’m going to give you a framework to get your exact tuning numbers before turning them on in production, as well as examples of the exact graphs you’ll need to monitor them.

Here’s what we’re going to cover:

- A general, pseudo-code example

- A specific example using Semian in Ruby

- The charts you need (and how to read them)

Audience

This article is aimed at fairly senior engineers, but that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t read it if you don’t have Senior in your title. This notice exists to let you know that you should give yourself some extra grace, seek a little extra support, and take your time. You can do it!

Below are some articles that would be good reading before attempting this article.

But I would love to know which sections you find particularly difficult. Please email me any feedback at chuck@newrelic.com, vosechu@gmail.com (please send to both!)

Related reading

For this article I’m not going to include anything about what circuit breakers and bulkheads are, because well written articles about these patterns do exist. Instead, I’m going to send you directly to some of my favorites:

- The Circuit Breaker Pattern

- The Bulkhead Pattern

- Tuning your Circuit Breaker (specifically about Semian, but generally applicable to others)

A general, pseudo-code implementation

Let’s start out with a general example that could be applied in any language. Because this is language agnostic, I need to start with one clarification:

Bulkheads and connection pools (with no queueing) are effectively the same thing. I’m going to refer to them as bulkheads, but please understand that outside of the Semian section, either one is possible.

Now, let’s look at the general pattern of how we’re going to find good numbers:

- Wrap every resource (network request, db, rpc, etc) with a method that sends some data to a timeseries datastore.

- Store that data for a couple of weeks.

- Find the longest period of time that doesn’t have any obvious incidents or oddities and adjust your time picker to only include that time range.

- Determine the maximum number of connections that happened in non-incident conditions, and configure your bulkhead/connection pool max to one more than that value.

- (Optional) If possible, find an incident and confirm that this value is low enough that it would catch and incident, but high enough that it doesn’t catch any traffic during a slight slowdown.

Sounds easy right? Let’s get started by finding that data!

The data you need to gather are:

You’ll need to send this telemetry, with the attributes specified below, to your timeseries datastore of choice. At New Relic, we send this data as events to NRDB, our timeseries database.

- Application name (After you’ve deployed it in all your apps, you’ll need a way to filter them!)

- Host name of the container or machine this worker is running on.

- Specifically, you need the hostname of the thing that’s going to hold the connection pool or the semaphore, so if you’re running containers on ECS, you want the container, not the EC2 instance that’s holding the containers.

- Resource name

- For Semian we use a string like

nethttp_authorization.service.nr-ops.net_443(Net::HTTP is the client library, then the url, then the port) - Whatever the format, this is the namespace that you want to isolate from all other namespaces, so be thoughtful about whether you want port 80 isolated from 443 or not.

- For Semian we use a string like

- Client library name

- For semian, this is called

adapterand is set to ‘http’, ‘mysql’, ‘redis’, etc. - This is useful because mysql and http work differently, so they’ll likely have different settings and different failure conditions.

- For semian, this is called

- Total number of current workers on this host.

- This uses the same definition for host as above.

- Current number of connections to this resource that are open and active on this host

- I’ll talk about how to get this in the next section

- Currently configured number of max connections

- I’ll talk more about this in the next section

- Current state of the bulkhead

- For Semian this is ‘success’, ‘busy’, and ‘circuit_open’

Probably the telemetry data is going to look something like this:

{

"appName": "RPM API Production",

"host": "api-grape-5fcbf68bcb-cgp74",

"resource": "nethttp_summary-record-service.vip.cf.nr-ops.net_80",

"adapter": "http",

"workers": "15",

"count": "14",

"tickets": "14",

"event": "success"

}

A specific example using Semian in Ruby

Implementation

I will now show you how this can be done in Ruby with Semian, and maybe that will help you understand how to do it in your language.

Semian is kind enough to give us a callback which fires every time Semian connects to any kind of supported resource, for both bulkheads and circuit breakers. We’ll hook into that first and use it to send our timeseries data.

For the example below, I’m going to only show network requests, but Semian is happy to cover mysql/postgres, redis, and grpc. They’re configured slightly differently, but the core ideas are going to be the same.

# config/initializers/semian_init.rb

if defined?(Semian)

Semian.subscribe do |event, resource, scope, adapter, payload|

bulkhead = resource.respond_to?(:bulkhead) && resource.bulkhead

semian_event = {

# The resource name

resource: resource.name,

# The configured max number of allowed connections

tickets: bulkhead && bulkhead.tickets,

# The current number of concurrent connections

count: bulkhead && bulkhead.count,

# The number of workers in this pool

workers: bulkhead && bulkhead.registered_workers,

# The state of the bulkhead/circuit breaker

# 'success', 'busy', or 'circuit_open'

event: event,

adapter: adapter

# Because this is going through the NewRelic::Agent, we will also get `appName`, `host`, and a couple other helpful things.

}

NewRelic::Agent.record_custom_event('SemianEvent', semian_event)

end

end

So that takes care of the data, but we also need to tell Semian which resources to actually watch. We’re going to start with a deliberately simplified version, then introduce some more complexity and flexibility later.

# config/initializers/semian_init.rb

if defined?(Semian)

SEMIAN_BASE_NET_HTTP_CONFIG_PARAMS = {

# This controls whether the bulkhead is on or not.

# Note: We need this on in order to get any data, but we can neuter it by setting the `tickets` to a high number.

bulkhead: true,

# This is the allowable number of concurrent connections by default.

# Note: Set this to the same number of workers on your machine so the bulkhead never triggers.

# If you're using a variable number of workers (Puma, Thin, etc), experiment with setting this much too high. But I've not tried this, and even when we run Puma we use a fixed 5 threads per process, with 6 processes per host.

tickets: 30,

# These two control the "X errors in Y seconds" that the circuit breaker uses to determine whether to trip.

# Note: Set the threshold to something _way_ too high for our initial research.

error_threshold: 1_000_000,

error_timeout: 1,

# When the circuit breaker is "half-open", how many successes do we need before we open the flood gates?

success_threshold: 3,

# True here means 5xx responses will raise circuit exceptions too.

# For now, while you're testing, you probably want it set to false.

# Note: Our team has it on, but it's a complicated problem. Read here for some rationale: https://github.com/Shopify/semian/pull/149#issuecomment-307918319

open_circuit_server_errors: false

}.freeze

Semian::NetHTTP.semian_configuration = proc do |host, port|

# Always good to have a toggle in case this doesn't work the way you expected!

return nil unless ENV['SEMIAN_NET_HTTP_ENABLED'] == 'true'

# This will wrap all external web requests with a bulkhead and circuit breaker, but the defaults should prevent the bulkhead and circuit breaker from doing anything.

SEMIAN_BASE_NET_HTTP_CONFIG_PARAMS.merge(name: [host, port].join("_"))

end

end

At this point, you should be able to ship this to some innocuous environment like qa or staging. If that goes well, delicately try it out in production. It shouldn’t do anything, but reality is rarely so polite.

Note: If you’re using Puma with a variable number of workers, you may need to make some serious adjustments. I haven’t tried it with a variable number of workers, but theoretically it could work. I would not recommend the quota method of configuring Semian, but you may need to do that.

The charts you need (and how to read them)

Looking at the raw data

Now that you have that running, execute the following query (or something like it) in your timeseries database:

SELECT *

FROM SemianEvent

This will output a few lines that look like this:

| App Name | Host | Resource | Tickets | Count | Workers | Event | Adapter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPM API Production | api-grape-5fcbf68bcb-cgp74 | nethttp_summary-record-service.vip.cf.nr-ops.net_80 | 15 | 14 | 30 | success | http | 87.3k |

| RPM API Production | api-grape-5fcbf68bcb-cgp74 | nethttp_summary-record-service.vip.cf.nr-ops.net_80 | 15 | 13 | 30 | success | http | 84.3k |

| RPM API Production | api-grape-5fcbf68bcb-cgp74 | nethttp_summary-record-service.vip.cf.nr-ops.net_80 | 15 | 12 | 30 | success | http | 82k |

Before we dig into how to use this data, let’s go over what some of these attributes mean:

ticketsis the maximum configured number of concurrent connections to this resource per host.workersis the number of processes/threads that are currently running on this host.countis the current value of the semaphore, counting down fromticketsto zero, which is the opposite of what we need. Also, it is 0-indexed while the rest start at 1.tickets - count - 1is how we calculate the current number of connections to this resource. This is the number we’ll eventually use for calculating the ideal bulkhead value.eventis the status of the circuit breaker or bulkhead; it can besuccess,busy(which means the bulkhead is mad), orcircuit_open(which means the circuit breaker is mad, but we don’t really know if it’s because of a bulkhead or something else).

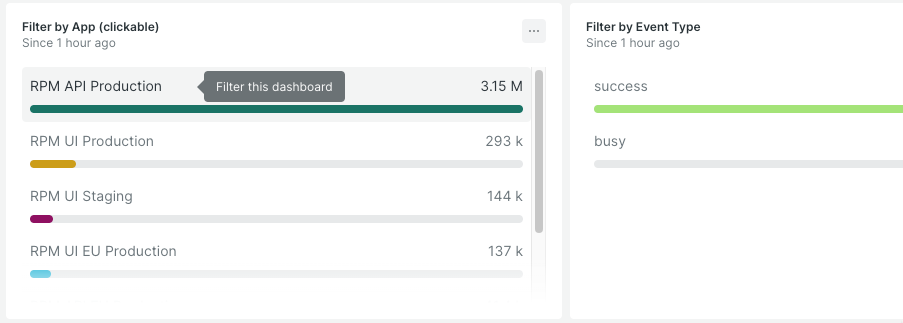

Filtering your data

To filter dashboards in New Relic, you can use the filter bar, but I would also like to recommend that you use template variables or facet filters. They make the process much easier.

Facet filters allow you to display a list of something and filter the whole dashboard by clicking on a value:

They’re generally very simple queries like this one:

SELECT count(*)

FROM Transaction

FACET appName

Template variables are a newer method that performs significantly better than facet filters, but it’s newer and it requires that the dashboard widgets be modified to use the template variables if they exist.

Finding a good baseline

Now that you’ve adjusted your filters to select only one Application and only one resource, we can work to find a good baseline time range.

I’ll use the following query:

SELECT

max(tickets - count - 1) AS 'Max connections',

percentile(tickets - count - 1) AS '0.1% traffic loss (99.9%)'

FROM SemianEvent

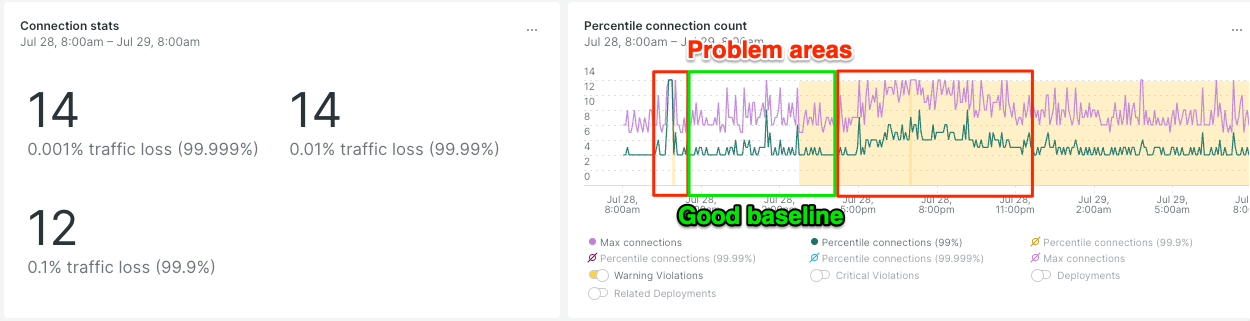

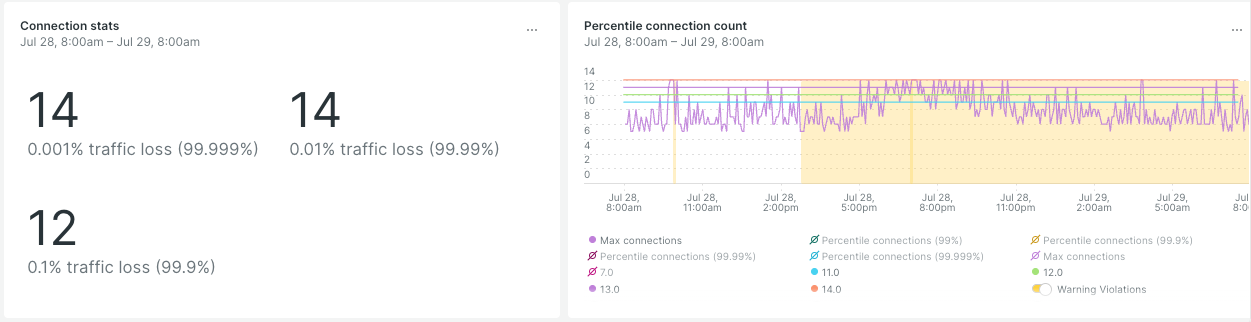

Note: In the following screenshots, that above query is the one on the right. On the left, you can see a sneak peak of the final query I’ll show you at the end of this section.

This is what those queries look like:

In the screenshot above, in the graph you should see that there’s a spike on the left side, which seemed to recover very quickly, and in the middle there’s a chunk of oddly high connections (and a warning in the background). Neither of these are great times to focus on, they are not “typical”, and that’s what we need right now.

We need to find the largest contiguous area that doesn’t have these little blips, so we can pick either the area to the left or the right of the hump. The area on the right is getting towards evening, so that may not be representative of reality. So in this case, I would pick the area to the left of the hump.

Realistically, this may be a bad day to look at, but I know this service pretty well, so I was able to. If you don’t know your services as intimately, it’s worth looking on other days to see if there’s any longer time periods and to see what “typical” really looks like.

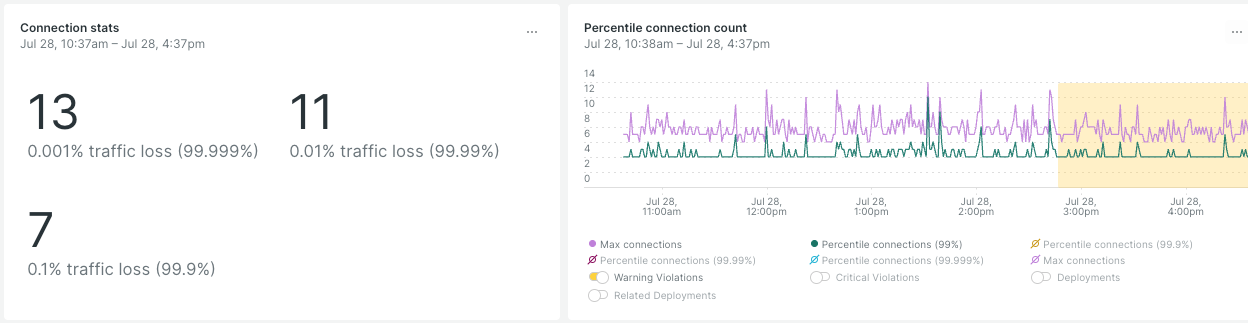

You can adjust your time picker, but in New Relic dashboards you can also click and drag over a section to zoom in. After zooming in, this is what the chart looks like:

The chart on the right feels a little flatter, though there are still some spikes. For now, let’s continue on with the activity.

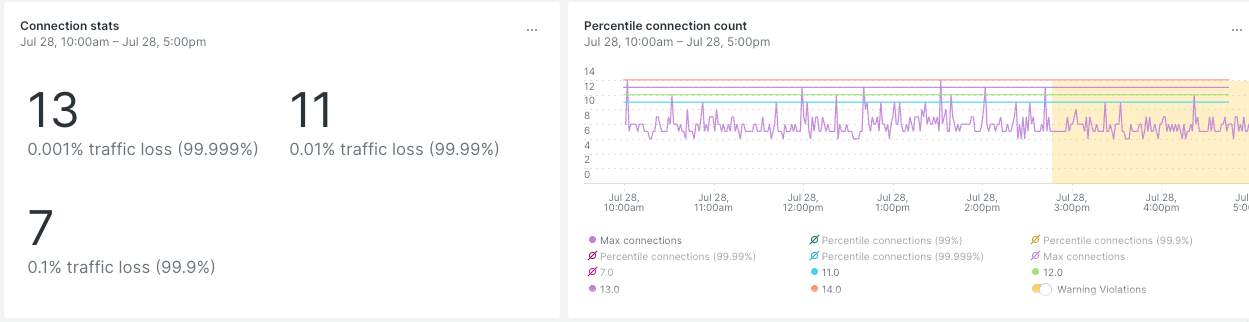

Let’s play a guessing game.

In order to really communicate the danger of picking bulkhead values at random, let’s play a guessing game. You’re going to try to guess the right bulkhead number based on some charts, and I’m going to show you how many angry customers will contact you if you choose wrong. Sounds fun right?!

I’m going to draw a series of lines on the chart from before. Each line will represent a different bulkhead config value, which means that all traffic above that number will be cut off.

I would like you to try to guess what percentage of your customers will receive 5xx responses because of each line. We’ll start with a bulkhead value of 11 and go up to 14.

Go ahead and choose a number that is:

- Higher than the maximum concurrent connections that your customers need.

- Low enough to prevent major incidents from getting worse.

I’ve only shown the max() connections, not a percentile, so if the number you chose is entirely above the wiggly line, 0% of traffic (during this period) would be cut off. So that would only be 14.

If you chose 13, 0.001% of traffic would be cut off during a baseline time. That’s pretty reasonable. My bosses are generally pretty happy when I can tell them that we’re getting 5 nines of availability (okay, that’s discounting non-baseline times, so hold on to your hat for a bit).

If you chose less than 13, that’s getting into pretty dangerous territory. 11 seems totally reasonable, it’s still 4 nines so only 0.01% of traffic would get cut off, but it’s traffic that really didn’t need to get cut off. Additionally, we’re assuming that our traffic is always like this, which it definitely isn’t.

Now let’s compare our numbers to the incident time range and see how we did!

Welp, unfortunately we don’t know how you did. It looks like the graph is cut off at 14 (which is what we have this resource configured at), so we can’t tell if the spikes would have gone higher.

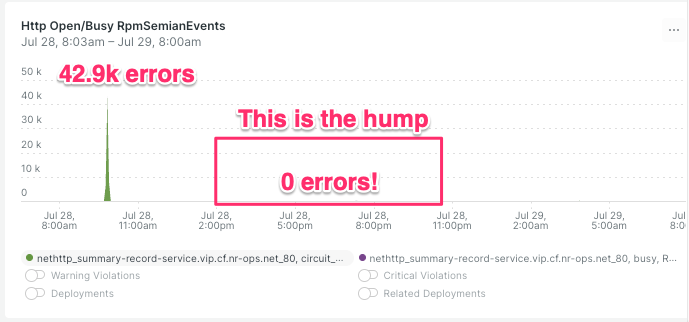

But we can look at the errors that came out! That should be a pretty good approximation!

Using the following query:

SELECT rate(count(*), 1 minute)

FROM SemianEvent

WHERE event IN ('circuit_open', 'busy')

AND adapter = 'http'

TIMESERIES MAX

FACET resource, event

This query basically gives us the part of the above chart that was cut off by the bulkhead. It looks like this:

So setting bulkheads to 14 for this resource seems to have been:

- Low enough to catch a huge spike and prevent that traffic from going through

- But not so high that a mild slowdown was enough to cut off a lot of customers! Huzzah!

This is why we need to get our numbers during the quiet baseline times, then check them against slightly abnormal times. Then we can decide whether we actually want to cut off those humps, or just the spikes, and back it up with hard data.

The final query that gets our bulkhead config value for each service

Please forgive me for not giving this query to you earlier. I really need you to understand that these numbers are hard stops, above which zero traffic gets through.

But now that you’ve gone through the entire doc above, I feel like I can trust you to use historical data to calculate an acceptable value that is low enough to catch incidents, and high enough to not cut off real customers.

Below is the query that was on the left side of all the screenshots above:

SELECT

round(percentile(tickets - count - 1, 99.999)) AS '0.001% traffic loss (99.999%)',

round(percentile(tickets - count - 1, 99.99)) AS '0.01% traffic loss (99.99%)',

round(percentile(tickets - count - 1, 99.9)) AS '0.1% traffic loss (99.9%)'

FROM SemianEvent

WHERE adapter = 'http'

FACET resource

From this chart, you can choose one of these numbers and put it straight into your pool or bulkhead configuration. There’s nothing more to it; you don’t need to pad it, though you can add 1-2 if you want.

What if the numbers are too high?

Note: If all of the numbers on this chart are the same (which happen to also be the same number as your worker count), it means that there is no acceptable number. You need more workers per host, or you need more workers in general (with more hosts to run them).

Note: The same is true if the numbers on that chart are above some acceptable limit (for instance, if you want to reserve 2 workers for health checks). The remedy is the same, you need more workers per host or more workers in general.

We had this exact problem in the beginning. In our case, we used to run 15 unicorn workers, and we wanted to make sure that 2 were left in reserve for health checks. So we didn’t want any services to exceed 13 tickets. Unfortunately, one of our services frequently reached 15 during baseline times. So we know that it is fully saturating all workers on one server on occasion; maybe our load balancing is off, or maybe it’s just bad luck. 13 tickets on 15 workers meant that we were reserving 13% of our capacity for health checks.

In order to address this, we doubled our instance’s memory and reduced the number of instances by half. Then we increased our worker count to 30 unicorn workers. This left us with the same number of workers in aggregate, but meant that any individual server could dedicate 28 workers to a task and still have 2 left over; 28 tickets on 30 workers meant that we were only reserving 6.5% of our capacity for health checks. It may not seem like a lot, but this was enough to get us through (for a while).

In the end, that service wound up with a cutoff at 28, which was 99.99% and that was judged to be good enough for that particular service.

Conclusion

I’m glad you could join me on this adventure! It’s been a wild ride, hasn’t it?

If you remember only one thing from this, I hope it’s this:

Tuning bulkheads requires historical information, and if you try to guess, you’re going to piss off your customers.

But I don’t want you to be scared off; this is a solvable problem and using historical data we can absolutely find viable numbers before going to production.

Once you have this deployed to production, you’ll need to continue to monitor these numbers. My team reviews them once a month, but also any time we change the number of processes/threads and any time someone introduces a new external service.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this post. Please email me any feedback at chuck@newrelic.com, vosechu@gmail.com (please send to both!).